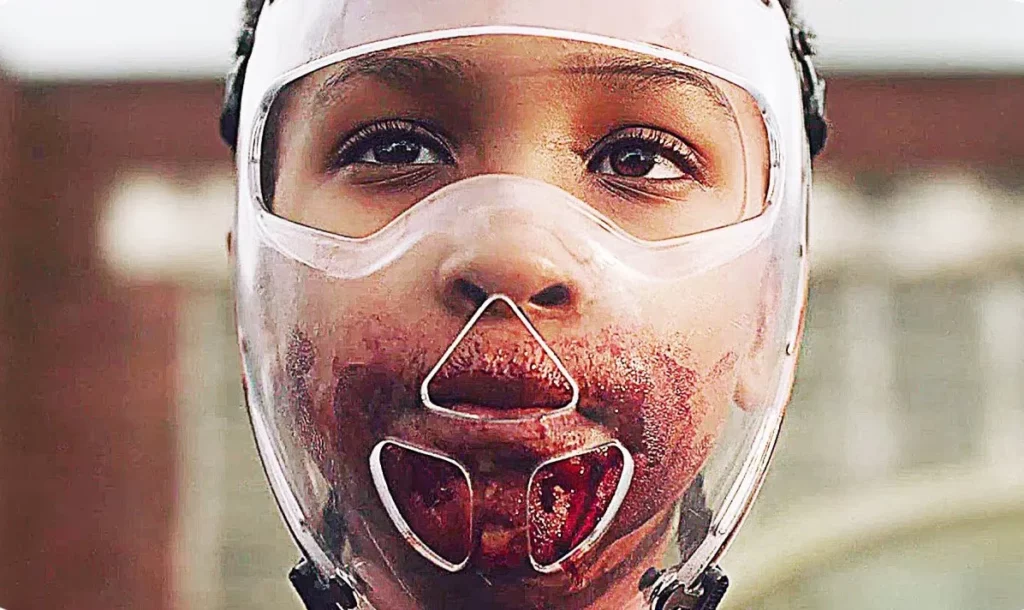

THE GIRL WITH ALL THE GIFTS (2016)

IMDB Synopsis: A scientist and a teacher living in a dystopian future em bark on a journey of survival with a special young girl named Melanie. Director: Colm McCarthy

Writers: Mike Carey (novel), Mike Carey (screenplay)

Stars: Sennia Nanua, Fisayo Akinade, Dominique Tipper

I’ve wanted to revisit the zombie genre since writing about sustainabil ty and (Romero’s) Dawn of the Dead in 2009 (the earliest form of this collection of short essays). Even as the Zombie fetish wanes culturally, there is no shortage of texts to chose from. Romero has pumped out more (true to his promise for a social commentary Zombie movie every decade), TV has embraced the plague, the Koreans are doing awesome crazy things with the genre, books have been written and made into films staring A-listers, American classics have been re-imagined, and sit coms revolve around the genre’s basic principles. Zombies have become satire of Zombies.

It’s tempting to look at the progression of the zombie genre and use that in and of itself as a lens to understand sustainability. For example, Zombies have morphed from lumbering oafs to hyper-athletes. Plagues have shifted from simple bite-born pathogen to chemical warfare, to water infestations, and even airborne fungi (poison plants adds an interest ing Monsantoesque commentary for the genre) Zombie blood has gone from red to black and back to bright red, sometimes more a reflection of the budget of the film, but even that is telling for a genre that started as low budget and ended22 with Brad Pitt – an obvious inverse of budget and quality. Even the role of the city in the genre has changed – city has hope, city as hell, city as very dangerous trip to a mall.

But THIS is the moment I’ve been training for…The Girl With All the Gifts based on the novel by Mike Carey.

On some level I hope this is my last Zombie lens. It won’t be. This movie is not about sustainability. It is about the relationships between generations and the responsibilities of one generation to another. It’s casting makes it about race and gender. Oh, wait, so yes – it’s TOTALLY about sustainability. Generational impact, race, gender: the broken building blocks of our broken culture.

Here’s the exact moment in the movie.

First the back story:

Post apocalyptic zombie-filled future. Glenn Close (Dr. Caroline Caldwell) is looking for a cure. Some children (dubbed neonates) seem to live in the space between being alive and being zombies – they don’t present as zombies until they smell human flesh, otherwise, they are just kids wearing muzzles. Melanie – our hero – is a neonate, and Glenn thinks she is the key to the vaccine for the fungal infection that creates zombies. Punctuating the film’s “playfulness” with generational responsibilities, neonates are born into this world by eating themselves out of their wombs (this is relevant but awesome).

Here’s the moment: In a pivotal scene near the end of the movie, Glenn is begging Melanie to sacrifice herself. Glenn needs Melanie’s spine and brain (whose the zombie here, anyway?) for the vaccine, and Melanie wants to know if she and her other neonates are alive or dead. It’s a yes or no question. It’s the existential question we all want the answer to.

In The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (Sophie Fiennes, 2012), Zizek confronts Morpheus from the Matrix, and Morpheus offers two pills – one pill (red), you stay in the Matrix, the other (blue), you wake up and get the truth. Zizek, insists on a third pill – one to see reality in the illusion itself. Basically, he wants the glasses from They Live.

Melanie wants the third pill too, and in swallowing it has the wisdom to confront the establishment – the old doctor.

Melanie: We’re alive?

Dr. Caroline Caldwell: Yes. You’re alive.

Melanie: Then why should it be us who die for you?

Well, isn’t that just THE question? What generation has the right to live according to their own rules at the expense of another generation? Do Boomer’s get to force Gen X into a set of morals or consumption patterns based on their “old” way of life? Do X to Y to Millennials? Do former generations own any responsibility for Climate Change? Do we? Will they? If so, what is that responsibility?

Yes, according to the Brundtland Commission definition of sustainability from 1987:

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the needs of future generations to meet their own needs.”

This is not Glenn’s position. Nor, is it Melanie’s for that matter. Each represents a kind of my-generation-first-and-foremost ideology that is the problem. And this has been coming for a long time. As soon as one side creates “Us” it becomes a matter of Us or Them. Statisticians are perhaps to blame by naming generations. There can be no compromise in modern politics and drama, it’s just not entertaining enough. And it is all entertainment, and teasing of a future return to some greatness. youth as hope

In keeping with the youth as hope trope, Melanie does emerge as a leader of a new generation of neonates before and after the fall. Half of the children have been schooled, the other half are feral. And, so the only locally remaining “full human” becomes the captive – Helen (Gemma Arterton), the teacher who saw something human in the neonates when they were the captives. At the end, she is trapped in a bubble by the children. And she is happy to teach them through the glass, to evolve them from within her cage. She is a living legend. The bubble protects her from the zombie-kids, of course, but it also serves as a re minder that the children need protecting from the generation that came before them. She, literally, becomes a kind of performance art, a muse um piece, a relic of what not to be. But with wisdom.

It can’t be ignored that all the powerful characters in The Girl with All the Gifts are women: Doctor Glenn, Helen, Melanie. Women are both the survivors and the “birthers” of the neonate zombies. Women bookend life, let’s not forget. The movie would be different if the evil doctor were a man. If so, we would quickly read – and as quickly dis miss – the relationships as a simple gender conflict. We would dismiss it because that’s what we do with gender conflicts – our court system is littered with examples of dismissal of our rape culture. By not utilizing gender conflict as a storytelling device, we are left with an opportunity to address it. We are also left with a space to view a companion dialogue about these generational responsibilities.

Zombies, everyone knows, are a metaphor for consumption as a way of life. Dawn of the Dead was a one-trick pony on that issue. And (here’s the point) generations consume different things in different ways. Where Boomers reveled into the single-serving paper plate culture, Millennials prefer to consume experiences. The Girl With All The Gifts pokes a finger in the chest of the concept of generational responsibilities – what does one generation owe the next and to what degree? Where Boomer’s preferred a kind of convenience culture, and Gen Xers are typ ified by pre-washed jeans and engineered vintage in an effort to appear authentic (Levi’s 2009 OPioneers! campaigned perfectly packaged all of this), Millennials are busy booking AirBnB vacations on the cheap to buy experiences. Honestly, the truth is that each of these – paper plates, manufactured authenticity, and awkward overnights in a stranger’s house are products of what Theodore Adorno called the Culture Industry.

“The Culture Industry piously claims to be guided by its customers and to supply them with what they ask for. But while assiduously dismissing any thought of its own autonomy and proclaiming its victims its judges, it out does, in its veiled autocracy, all the excesses of autonomous art. The culture industry not so much adapts to the reactions of its customer as it counter fits them.” (1951, Minima Moralia: Reflections for Damaged Life). In 1951 Adorno predicted green marketing.

And while I instinctively cringe at the birth of a new kind of generational tagging system such as the recent advent of Xennials (a microgeneration between Gen X And Millennials), I must admit that my cringe is based on a quick reading of “poor snowflake Millennials need an even narrower definition of themselves, and yet hate being labeled.” I would, however, regrettably welcome Xombies as a thing. Even the phrase microgeneration reeks of a culture that demands customization at every turn. And good for them. It’s possible, so take it. Own it. They (a dangerous word) are not choosing between the red and blue pills. They are experiment ing with a third it seems. “I’m not this or that generation, I am both and neither, now stop labeling me.” I’m aware that I sound like an angry Gen Xer, and there’s a good reason for that. He/she/they/it/we become us.

All generations seated inside capitalism are living inside Adorno’s Culture Industry. But, looking at how these cultures are evolving within that economic system gives me a sense of hope (by definition, all hope is based on false hope, by the way) that the next generation is doing it bet ter. I see this everyday in my own children. Of course, there is no such thing as ethical capitalism, or conscious capitalism, or capitalism with a human face. It’s all capitalism with a mask on. It manufactures desire, it does not alleviate suffering, only the feeling of alleviating suffering. “Enjoy your symptom,” as Zizek put it. I think Melanie’s mask might be the best mask for capitalism to don.

A smarter quote might come from Naomi Klein:

Our economy is at war with many forms of life on earth, including human life. What the climate needs to avoid collapse is a contraction of humanity’s use of resources; what our economic model demands to avoid collapse is unfettered expansion. Only one of these sets of rules can be changed, and it’s not the laws of nature.

So, it’s not so much that generations create desire as they have that desire manufactured for them. By what? Pop Culture to a huge degree. Zizek agrees, and said that film is the most perverse art form because it doesn’t give you what you desire, it tells you what to desire. And I desire more films like The Girl With All The Gifts. Pop Culture CAN be used as a change agent of sorts, independent Art has always had this responsibility, if not potential.

The Girl With All The Gifts, offers a beautiful allegory to expose the potential power of generational change, the tension of Now v Then, Us v Them, and the patriarchy’s failings. It is one of the best I have ever seen. Here, admittedly too late, I return to gender.

If we replace “zombies” with “sustainability”, I can imagine a girl (not a corporate art “defiant girl” but the same stance), a scientist, or a political leader, an artist, who steps up to save the world from Climate Change. This is a romantic fool’s notion, I know, but humor an old man coming to his senses. To do so, she would have to destroy the past in all but a sense of lore – put put the past in a box. In a place where we could learn from it, but it could not touch us. Religious patriarchy taught is dominion over the earth. It’s time to put that and other manifestations in the box. But the truth is, there is no head-strong girl coming to save us (help us, Stormy, you’re our only hope). Nope, there are millions of women already at work…in companies, in middle school science fairs, in local governments, in Art galleries. We (I am specifically pointing at myself as a member of the patriarchy), simply need to step aside, and (unlike Glenn), chose to not kill them.

22. I consider World War Z the end of the zombie movies I grew up with. I am 48.